Guidance: general structure of national regulatory frameworks

In this section we explain the importance of national level legislation. We give a basic explanation how national legislative systems are designed, and we provide guidelines how to find the legislation that is important for BwN.

The previous section shows examples of international regulations. Next to this, the European Union has developed an extensive body of legislation which is binding for EU Member States.

Here, however, we argue that the most relevant level for BwN projects is the national level. This is due to the principle of the ‘sovereign state’. The political authority of a sovereign state has a mandate to govern the people and the resources within its territory, without interference of other states. The principle of the sovereign state was created at the time of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 with the aim to reduce endless wars between European states. From then on, religious or economic reasons were no legitimate reasons anymore to start a war with another country.

Presently, 193 sovereign states are a member of the United Nations. A sovereign state can only function fully on the international stage when it is recognized as a sovereign entity by other states.

National laws are binding for all citizens within a state. Every country has its own regulatory system in which it can choose to implement international law. The section on international frameworks shows how many sovereign states have endorsed each of them, to a maximum of all 193 member states of the UN. Of course, EU legislation is more binding; but even then it is quite difficult to correct a Member State when it deviates from what was agreed within the EU.

The governance system within most democratic states is further divided in three parts: the legislative power (a parliament that makes laws), the executive power (executives like ministers and a bureaucracy who implement the laws) and the judicial power that interprets the laws in cases of conflict. This division of powers, also called the ‘Trias politica’, is a social invention of Montesquieu, published in 1748. It was meant to prevent the concentration of power among too few people (until then, power was often concentrated in a monarch). Although the Trias politica may be common knowledge, it is important to consider this and focus on the power that matters most to BwN projects: the executive power. Legislative powers may come into play when a large budget needs to be approved for new infrastructure. The juridical power comes into play when parties who oppose BwN alternatives go to court. The best way to deal with this is to try and prevent this kind of conflict together with the executive powers.

The next step is the most challenging one: to explore which existing laws are applicable to a BwN project. Present-day regulatory systems are often organized by sector and therefore fragmented. Because of the sectoral organization of laws, BwN initiatives are confronted with many rules and standards at various levels. How to find the laws that are most relevant for BwN? The simplest answer is to hire legal expertise. It is also good to ‘know the law’ yourself. Domains that will be relevant:

- Water law (who owns it and how is it managed)

- Land use / spatial planning law

- Environmental law (soil, waste, building materials)

- Nature conservation law.

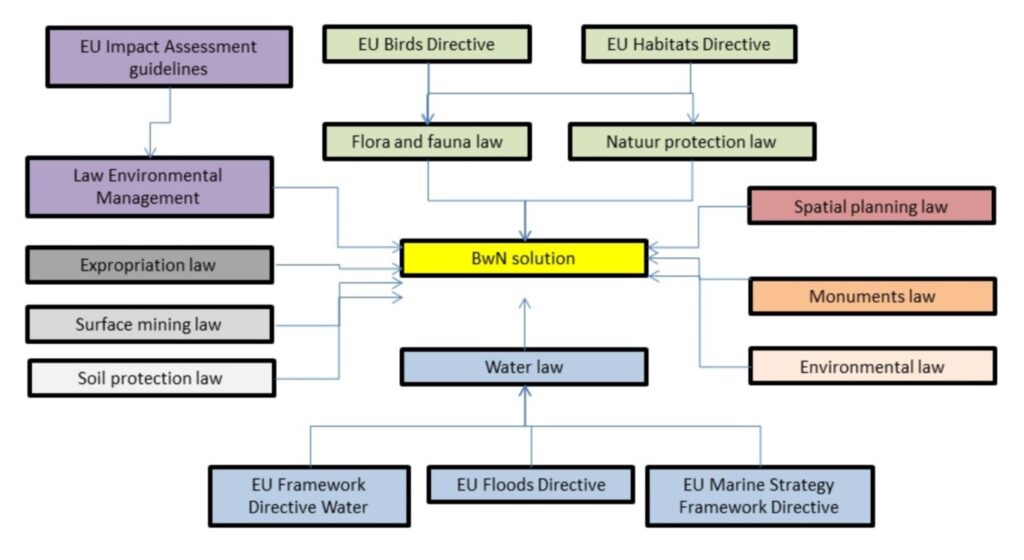

The figure below shows an example of a scan which Dutch and European laws and regulations can influence a BwN project. European legislation is generally taken up in the national laws but still the picture is complex and ‘food for experts’.

A developer should monitor closely whether a BwN design fits into the prevailing legislation and regulations. The check on legislation and regulations includes obligatory approval procedures (permits and licenses). The wide range of applicable laws is reflected in the multi-stakeholder approach that is needed in a BwN project (see also the Enabler Multi-stakeholder approach). Even different departments from one institution may need to communicate and work together to implement a BwN project. These different stakeholders will also be able to help with sorting out parts of the legislation with which they are familiar.

Many laws have an enabling character: they support human activities, as long as they stay within responsible boundaries. Examples of such enabling legal frameworks are spatial planning laws and agricultural laws. Nature conservation law is an exception. It seeks to protect natural values against human activities; therefore, it can pose significant barriers to new developments. Even if BwN is potentially beneficial for nature, nature laws can become a barrier; especially when an actor in the field opposes the BwN activity and goes to court. In the next section we provide more detailed advice how to deal with (EU) nature conservation laws.

Although a good analysis of the relevant legal system will be of great help, it still is not the whole story. Interpretation of laws is not mathematics. Dealing with formal regulations means navigating between two bad extremes: on one side, totally ignoring the regulations would result in complete arbitrariness and ‘lawlessness’; on the other side, using regulations as a strict blueprint would freeze a society in one orthodox shape. Between these extremes, interpretation of laws is an ongoing process. Because our views on reality change, and the world itself changes, the regulatory system also needs to be adapted on a regular basis.

Next to the visible, written law, there also are tacit, invisible, cultural rules in every country. These cultural rules influence how countries use their formal regulations in practice. Countries may, for example, prefer strict enforcement, or have no enforcement at all. It may be a habit to go to court at the slightest incident, or people may try to avoid a court case at any cost, preferring endless negotiations (‘polderen’). In many countries, two parallel regulatory systems exist; for example, an old one, based on traditional religion, and a new one, based on the market economy. In most countries it is wise to not only study the legal texts themselves, but also observe the tacit rules as well as the local attitude towards legislation.

Interaction with nature conservation laws

In this section we go deeper into nature conservation law, because in the European context this was identified as the most difficult type of law to tackle for a new development. When exploring nature law on other continents, be aware that such legislation builds on other legal frames without mentioning them. For example, the property rights of land and water resources may be arranged in a totally different way compared to Europe. Or indigenous peoples such as Sami, Inuit or Maori may have different rights than other citizens of a state. An internationally working organization like the World Wildlife Fund will have good insights in the nature legislation across the globe, and may be a good partner on this aspect.

European nature regulations aim at conservation of ecological quality. The EU Birds and Habitats Directives, established in 1992, form the legal basis for Natura 2000 network of protected areas. The Birds Directive also protects species outside of designated nature areas. Unfortunately, these directives do not have a dynamic perspective, even though nature itself is quite dynamic. The basic assumption is that too much nature has been lost, and what remains should be defended at any cost. It is not sufficient for BwN to argue that important new nature will develop due to a project. Within the present legal system, BwN must argue that it will protect existing values and will add new values.

Still, if a developer approaches regulations as opportunities, he/she could try to make optimal use of them. There are several reasons to perceive the EU Directives as opportunities instead of barriers:

- Guidance documents published by the European Commission encourage BwN in estuaries and coastal zones, port development and inland navigation (European Commission, 2011, 2012).

- Case studies and BwN pilot projects show that BwN-type developments are possible within the existing regulatory framework.

- When protective measures against flooding of human settlements are needed in a nature area, BwN has a great opportunity to play a role. Based on the legislation, BwN can compete better with traditional measures in nature areas than outside of nature areas. Outside nature areas there is no incentive to take the ecological system into account.

- In cases where funding for ecological project-components is limited, environmental regulations could serve to ‘push’ for a BwN-approach to live up to environmental obligations (e.g., the goals of Natura 2000).

Habitats Directive Article 6

Article 6 is one of the most important articles in the Habitats Directive as it defines how Natura 2000 sites are managed and protected.

Paragraphs 6(1) and 6(2) require that, within Natura 2000, Member States:

- Take appropriate conservation measures to maintain and restore the habitats and species for which the site has been designated to a favorable conservation status.

- Avoid damaging activities that could significantly disturb these species or deteriorate the habitats of the protected species or habitat types.

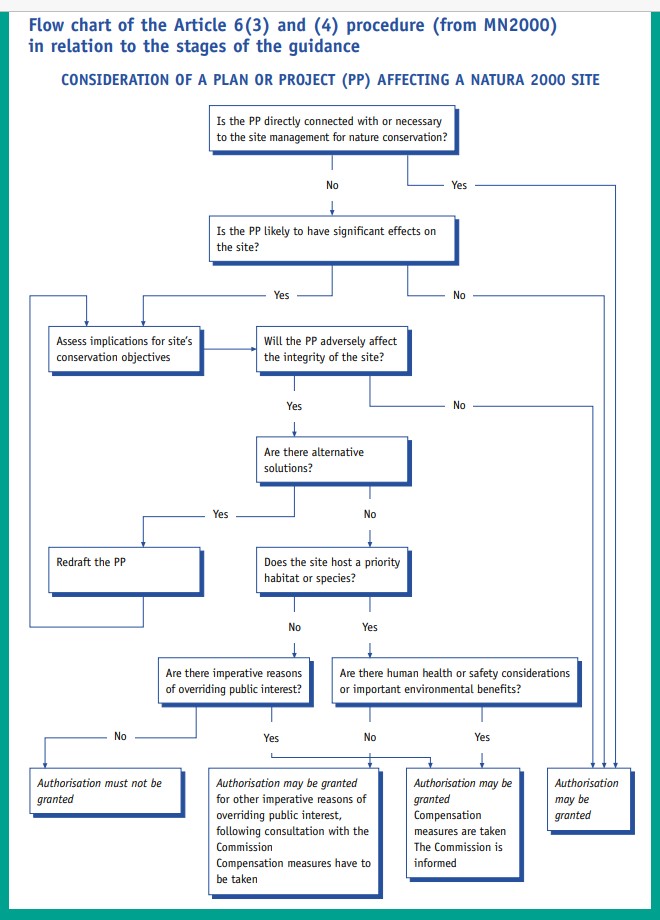

Articles 6(3) and 6(4) lay down the procedure to be followed when planning new developments that might affect a Natura 2000 site. Thus:

- Any plan or project likely to have a significant effect on a Natura 2000, either individually or in combination with other plans or projects, shall undergo an Appropriate Assessment to determine its implications for the site. The competent authorities can only agree to the plan or project after having ascertained that it will not adversely affect the integrity of the site concerned (Article 6.3)

- In exceptional circumstances, a plan or project may still be allowed to go ahead, in spite of a negative assessment, provided there are no alternative solutions, and the plan or project is considered to be justified for imperative reasons of overriding public interest. In such cases the Member State must take appropriate compensatory measures to ensure that the overall coherence of the N2000 Network is protected. (Article 6.4)”.

Once the regulation scan has identified Natura 2000 areas in or around the proposed project location, there are two main courses of action to fit a BwN design into the corresponding regulatory requirements.

The first course of action is to exclude significant adverse effects in the pre-screening phase of a project. Likely, BwN can be helpful to improve the Natura 2000 area, or at least stabilize it. The following questions may be helpful during this stage:

- Can we adjust the BwN design so that it contributes to the Natura 2000 conservation objectives?

- Can we make our BwN initiative beneficial for the management of Natura 2000 sites?

- Can we split the BwN design and realize it in separate stages (sub-projects), while keeping in mind the cumulative effect on Natura 2000?

- Can we upscale or downscale the BwN initiative to safeguard overall coherence of the Natura 2000 network?

An outcome of such adjustments could be a BwN design that supports the favorable conservation status of the protected habitats and species. If this is the case, the chances of its approval by administrative court in case of appeal are high.

The flow chart shows the main steps in decision-making in Natura 2000 protected areas according to Art. 6 of the Habitats Directive.

- For areas with a special conservation status the overall positive ecological effects of BwN on protected species and habitats will usually exceed the (temporary) negative effects of the project measures (i.e., land reclamation), in line with the goals in the area. A well-founded case must be delivered, with explicit reference to the conservation objectives of the area.

- The assessment of ecological effects at pre-screening stage (see diagram: pre-screening and BwN design) must emphasize the BwN idea of a project. BwN measures do not threaten the favorable conservation status of habitats / species, and often even support their recovery and/or improvement. The purpose of a pre-assessment stage is to investigate the possibility of significant negative effect and determine whether appropriate assessment would be needed. If significant effect could be avoided with the help of BwN design at this stage, the project can proceed.

- Once agreement on this positive effect of BwN has been established, the developer should be consistent in the use of terminology and avoid terms like ‘appropriate assessment’ and ‘compensation’, which come at a later stage but only in cases with a negative effect.

- If the pre-screening convincingly rules out significant effects or demonstrates that they are negligible, an appropriate assessment procedure is not necessary, even when a project implies the loss of Natura 2000 area (see example project Zeewolde).

The first course of action described above aims at preventing or compensating for damage to nature in Natura 2000 areas. The second course of action can be used if adjustments in the pre-screening phase still imply significant negative effects. If there is a chance of significant negative effect, the project should proceed with an appropriate assessment (see diagram: Art. 6.3 Appropriate assessment) or further according to Art. 6.4 with alternatives assessment, compensation plan and Statement of Imperative Reasons of Overriding Public Interest (IROPI). In this case it needs to be argued that the BwN project is an intrusive development, but it is of overriding public interest. When BwN is implemented for the water safety of a great many people, for example, an authority will likely see this as an important public interest. In such a case, a permission may be granted, but compensation of natural values will be demanded at the same time. In the absence of alternative solutions, possibilities could be explored to realize BwN principles alongside a compensation plan. Another opportunity arises when another development ‘with overriding public interest’ needs a compensation plan. Then BwN could be implemented as part of this compensation plan.

Next to adding value to nature, BwN may look for local stakeholder support through further spatial development. BwN can provide a platform for cooperative interaction among stakeholders and implement recreational options or solve existing spatial issues. Such a process will prevent local resentment and legal fights later on. Stakeholder interaction should start when it becomes clear that a compensation plan is unavoidable. The following questions may be helpful at this stage:

- How can BwN compensate for the impact on natural values?

- What are the possibilities for BwN as part of the compensation plan of another development?

- Can we adjust the BwN design to benefit local stakeholders’ interests?

- Can we use BwN to facilitate cooperative interaction among stakeholders?

While negotiating about these options, a project developer should make clear that BwN solutions are flexible and steerable. This means that action can be taken when there appears to be a negative impact on nature. Do not hesitate to interact with regulators, who are often frustrated by counter-productive fragmentation of rules and are quite willing to look for solutions. After the first meeting, stay in contact with the authorities and update them of important steps in the BwN project development.

BwN projects outside of nature areas

Of course BwN projects can also be realized outside of Natura 2000 areas; and increase natural values there. In those other locations, other regulations might apply, which can be less strict, but key is to look for the opportunities in those regulations that address the multiple policy goals of governmental bodies.