Guidance: innovative procurement and contracting for BwN

We now move from public law to private law. Public law governs the relation between individuals and the state, while private law governs the relations between individuals. Public law is difficult to change, and it is often more productive to just try and fit within the existing public law. For private law this is different. BwN developers can re-invent contracts until they fit their needs. Of course overall rules from private law will still apply, such as rules for fair competition on the market (public procurement law) and general legal principles like pre-contractual good faith.

Innovative procurement and contracting is needed for BwN for three reasons.

- BwN often is a multifunctional solution. BwN includes extra benefits for nature and society, next to providing the primary function of hydraulic infrastructure. This implies BwN solutions cannot be evaluated on monetary costs and benefits alone.

- Multifunctional solutions often also imply multi-stakeholder involvement. Arrangements between more than two partners make it more complex.

- BwN is a dynamic solution requiring monitoring and maintenance.

These aspects make traditional procedures difficult to apply. What this means for BwN is further explained below.

Innovative tendering procedures for BwN

Governments and other project developers have to follow a tender process in case of outsourcing works and contracts. The rules, procedures and requirements for this are easily traced in national legislation. Typically the bid process includes a prequalification step or integral qualification criteria; usually criteria include financial qualification for similar work, technical qualification and the financial eligibility of the contractor, expressed in terms of total turnover. Such rules, that frame competition and determine who is eligible, influence the lineup of private parties such as consultants and constructors.

Because traditional tendering may almost exclude the option of Building with Nature, it is wise to contact a government in an early stage and point out the need for a more innovative procedure. Innovative contracting inevitably includes a certain level of uncertainty in early stages of decision making. The procedure may consist of five phases:

- A team of experts analyses the situation and reports it in a short document. The analysis comprises water security risks but also a stakeholder analysis and an overview of opportunities as seen from the different perspectives of these stakeholders.

- The government plans the further procurement procedures based on this analysis. The analysis is used to formulate important criteria for selecting tenders.

- Procurement starts with pre-selection of consortia. Suppliers position themselves on price, knowledge and competences. One or two consortia are selected.

- The procurement procedure continues with a negotiation about handling risks and opportunities. During a ‘process of dialogues’ the plan is further defined and pricing is agreed upon. In this phase trust needs to be built so that the consortium and the government are willing to take on future risks together. Projects with multiple objectives may trigger additional resources and co-financing.

- A contract is signed and the construction can start.

If the award criteria are made on the basis of Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT) this helps the selection of BwN solutions. In the Netherlands the Tendering Rules Works law was changed in 2016 in favor of ‘Best Value for Money’. In every tendering procedure specific quality criteria are defined regarding public usefulness, sustainability and risk management. The score on these criteria weighs at least as much as the price in selecting the winning consortium.

The selection criteria also should be designed conducive for BwN. Some important aspects:

- Instead of the traditional technical specifications, sound functional requirements need to be formulated, based on system engineering. The functional requirements at least include spatial and time boundaries. The criteria should anticipate subsequent steps in working towards specifications for implementation.

- Define and describe the process: clearly state who is responsible for what, the set of performance indicators as agreed upon, how compliance to performance indicators is measured, the allocation of risks over partners and the pain and gain settlements. Be aware that these monitoring, verification and accounting schemes should be regularly updated while the consortium works itself through the project phases.

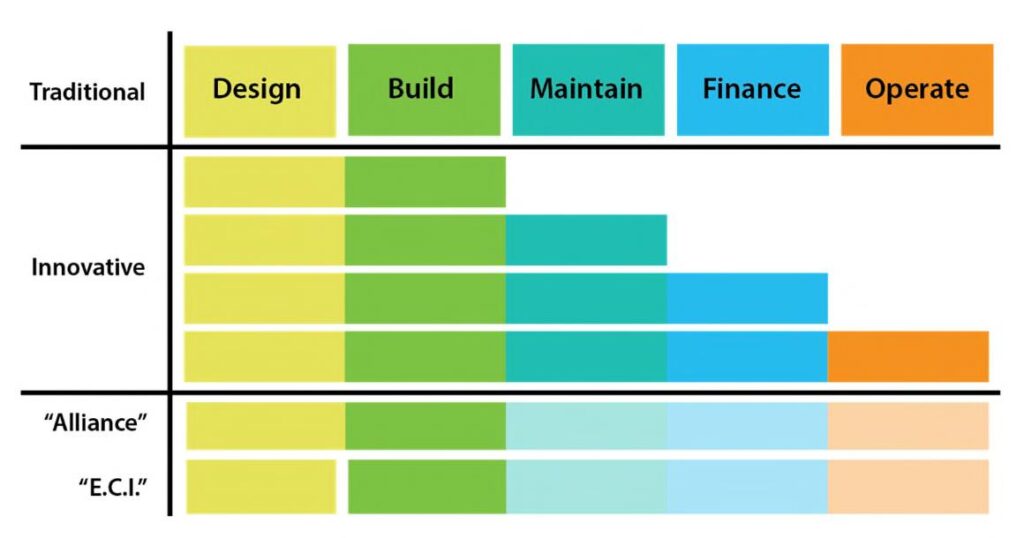

In the criteria the life cycle costs of a solution are taken into account. The contract extends itself to the maintenance phase (see figure).

From traditional contracts to multi-stakeholder arrangements

In a conventional contract, there is a clear distinction between the construction phase and the maintenance phase, with separate contracts for each phase. The construction phase requires the biggest investment, and costs for maintenance are limited. Ideally, people need not worry about it for the next fifty years. In a BwN solution, the weight of the costs shifts from construction to maintenance (see also the Enabler Business Case). A contractor is involved for a longer period and is responsible not only for construction, but also for maintenance and monitoring of the natural processes that follow. In this maintenance phase, co-benefits play a role, and thus a multi-stakeholder contract might be needed.

The following contract arrangements are commonly used for the implementation of hydraulic infrastructure projects:

- Design only / build only. In this traditional model the project proponent asks engineering consultants to produce a design, and then a contractor is selected to construct it. Selection can be based on price only or on Best Value.

- Design and construct, possibly extended with Finance or Maintenance elements. Contractors have responsibility for both the design and the construction. Market parties compete on their ability to develop and design water infrastructure, in combination with cost-effective realization. Being able to identify and control risks is an important competence of the contractor.

- Performance Based Contracting (PBC). The contractor is responsible for the functioning of a system for a longer period of time. Payments are linked to a set of clearly defined performance indicators. Potential advantages are increased efficiency and room for the contractor to develop innovative solutions.

- Public Private Partnership (PPP), Alliance contracts. In this model, not only engineers and contractors are involved in a contract, but also governments, and sometimes NGO’s. They collaborate through all phases from project preparation, design, construction to maintenance. The constructor is involved in the design process; the government may attract financiers or loans to the project, and the NGO may assist in communication with stakeholders. They also share in the risks and opportunities.

More innovative contract arrangements can take more time to realize, but in some cases it can even speed up the process, as happened in the Netherlands with the Marker Wadden.