Overview

Abstract: Controlled moving primary high water-defence lines to more inland positions is a suitable method to prepare for increasing water levels in future.

Landscapes: Sandy coasts, Rivers & Estuaries

Technology Readiness Level: 9 (several successful applications completed)

Keywords: shoreline protection, controlled retreat, intertidal planes, ecosystem integration

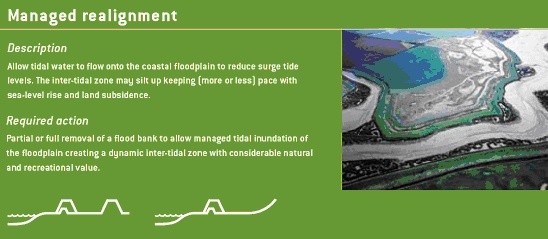

Controlled inundation of land by setting back sea defences is an increasingly used method for coastal protection and anticipation to climate change. In the United Kingdom this so-called “managed realignment” is applied widely and considered a cost-effective and sustainable response to loss of biodiversity and sea level rise. It is also applied in other countries such as the United States, Germany and Belgium.

By re-inundating land the coastline is placed backwards and new intertidal area is created. The area is enclosed by a secondary dike on the landside to ensure safety of the hinterland. The goal is to create the right circumstances for succession of saltmarsh vegetation. Once saltmarshes develop the vegetation will enhance sedimentation and the area will become higher and is able to grow with sea level rise. Saltmarshes can reduce wave energy and improve the stability of the dike.

Managed Realignment can be applied to many different situations that fall within the scope of coastal and flood management. Succes is also dependend on local boundary conditions. It is important to be clear on the aim and purpose of the proposed project at the beginning. Without this it may be difficult later to determine the success/failure of the scheme in meeting its objectives. It is also important at the outset of a project to identify any potential opportunities and/or constraints. Managed Realignment presents the opportunity for a variety of benefits, though such opportunities may also have associated constraints.

Concept

Definition and objective of managed realignments

Controlled inundation of land by setting back sea defence is an increasingly used method for coastal protection and anticipation to climate change (French 2006). In the United Kingdom dike setbacks, called “managed realignment”, is more and more applied and considered as a cost-effective and sustainable response to loss of biodiversity and sea level rise (Garbutt 2008). It is also applied in other countries such as the United States, Germany, Netherlands and Belgium. By re-inundating land the coastline is placed backwards and new intertidal area is created. The area is enclosed by a secondary dike on the landside to ensure safety of the hinterland.

Managed realignment is mostly used in low lying estuarine and coastal areas to counter-act coastal erosion and coastal squeeze as a consequence of sea level rise or other causes and improve coastal stability. Furthermore it is a method that is used to compensate for loss of intertidal areas (tidal flats and salt marshes) and as water retention area during extreme water levels in narrow river mouths.

A clear definition of Managed Realignment is given by Rupp et al (2002):

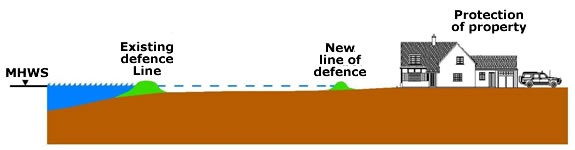

Managed realignment ‘involves setting back the line of actively maintained defences to a new line inland of the original – or preferably to rising ground – and promoting the creation of inter-tidal habitat between the old and new defences’

Managed realignment and wetland restoration are the same. Although minor differences exist. The word managed realignment is generally used throughout the UK and Europe for projects in which the safety against flooding is enhanced and ecology is incorporated. The word wetland restoration is generally used in the USA for projects in which the state of the ecosystem is enhanced, with high water safety as an added bonus.

A very clear explanation of a Managed Realignment is shown in this animation:

Project solution

How does it work, some examples

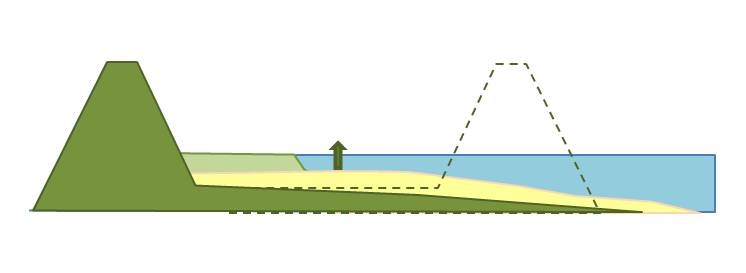

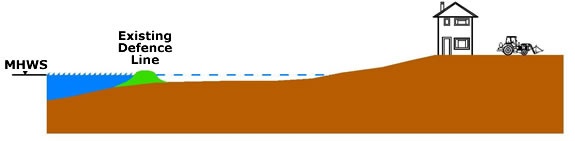

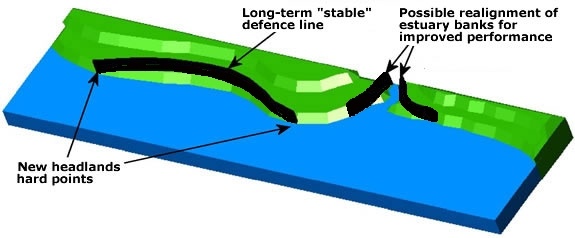

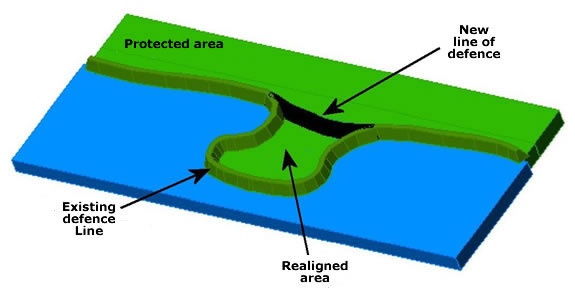

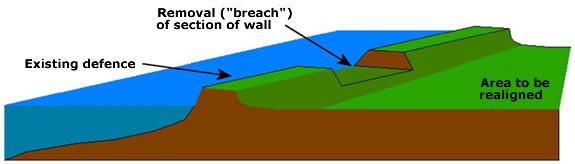

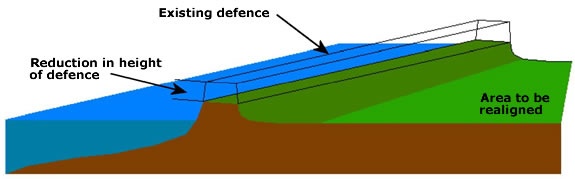

The figures below (based on figures from CIRIA, 2004) show examples of the different approaches to Managed Realignment .

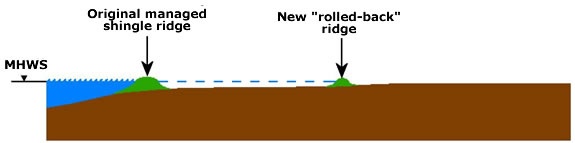

Retreating to higher ground is when a line of defence is breached or removed as there is higher topography behind the old line of defence. This allows the landward migration of the shoreline up to the higher ground and may produce a new intertidal area.

The planform of a coast or an estuary might be modified to improve the overall functioning (hydrodynamics) of the system or provide a more sustainable position (for defences and habitats). The nature of change will depend on the situation but might include the creation of a stable bay form on the open coast, or the modification of an estuary to move it towards an equilibrium form or to accommodate increased tidal volumes as a result of sea level rise. Consideration might be given to a number of separate realignments within an estuary to improve management of the whole system or allow present land uses to continue. The separate realignment methods that can be used are presented below.

Types of realignment

Design can greatly differ amongst managed realignment sites, depending on goals (coastal protection, nature development, retention) and specific local conditions. Pontee (2007) distinguishes three main types: banked realignment, breached realignment and regulated tidal exchange.

Breaching the line of defense (Breached realignment)

A Breach Managed Realignment allows the inundation of the land behind through a defined gap (‘the breach’). This option may be a desirable option to control inundation of the area or the flows from it. Such a breach may also be armored if it needs to be maintained for a long time. Simple dug breaches can be cost effective and provide a degree of protection (for example from waves or wash) to the landward area or allow longer residence time for sediment settling while the new intertidal area develops. The exit velocity of water will need to be considered carefully in terms of scour to seaward or impact on navigation. Pipes with tidal flaps, or other control structures, can be placed through a defense. These can be used to allow an intertidal area to develop and/or gain height (as sediment in suspension settles out) in advance of breaching the defense and are called tidal exchange systems.

Lowering or removing the line of defense (Banked realignment)

In some circumstances, the best option will be to remove the defense completely to allow a fully natural system to start to develop immediately. This is called banked realignment. This approach can be useful in managing the effects on estuarine processes or to provide wider intertidal areas where beaches are steepening. They can also reduce scour or navigation problems that may be caused by breaches. The reduction in defense height may be to ground level or to a slightly higher elevation to provide a sill that erodes down gradually and can encourage sedimentation to the landward side. The height of a defense may also be reduced, rather than removed entirely, to allow land use to continue for at least part of the time with a reduced standard to the flood defense level.

Regulated tidal exchange

Use of a culvert/sluice system in the coastal defence enables regulated tidal exchange to the re-inundated area. A high level and low level sluice in the dike enable inflow during high tide and discharge during low tide. The position of the sluices in the dike determines the tidal regime in the area. In a river mouth where fresh as well as salt water influence is present the sluice positioning and design can also determine water quality (salinity and nutrient) inflow (Maris, Cox et al. 2007) and determines the amount of water and sediment inflow. Regulated tidal exchange is mainly used for water retention motives, for example along the freshwater tidal zone of the Scheldt estuary (Belgium), where more retention is created by allowing reduced tide and dike overflow at several sites along the estuary. However potential of these sites concerning sedimentation and the ability of the area to grow with sea level rise also looks promising. By limiting currents and wave action, limited erosion occurs (Peeters, Claeys et al. 2009). Because water depth is not determined by the natural feedback (increase of elevation means decrease in water depth when inundating) but remains constant, continuous high sedimentation rates are possible (Vandenbruwaene, Maris et al. 2011). Vandenbruwaene (2011) calculated that an area with regulated tidal exchange could grow up to 2-2,5 times faster than a natural saltmarsh over 75 years. Drawbacks are high construction costs due to the sluices and limited exchange with the estuarine ecosystem.

Why managed realignments, what are the options?

Traditional design

Do nothing

This is where no action is taken to either improve or maintain the existing defences. This involves stopping all maintenance, repair, renewal, and emergency repairs. The defences may be monitored (for example for health and safety reasons) until they eventually fail, or a new management option is selected. The areas protected by the existing defence would no longer be protected from flooding once this management option is implemented and completed. Application of this management approach may require a defined and agreed exit strategy appointed under the permissive powers of flood risk management.

Do minimum

This involves limited intervention. Maintenance and repair works are only undertaken in an emergency for immediate health and safety issues. This will eventually lead to a reduced standard of defence over time. Under sea level rise, this may in effect be the same as lowering the defence level in relation to water level and thus provides a lower standard of defence over time.

Advance the line

This is where the line of existing defence is advanced forward by building new defences in front of the existing defences. This approach is only likely to be relevant on advancing or emergent coastlines but in such circumstances investment in new defences is unlikely to be warranted. Where infrastructure or development of national importance is required, it may be necessary to advance the line to meet the requirements of the development.

Hold the line

This is where the existing defence is maintained. This is achieved through repair, maintenance, and/or improvements to the existing defences. The standard of defence should be maintained with this option. This often calls for new works to be undertaken due to changing flood risks dependant on the area. Holding the line restricts natural processes, and is a leading factor in the growing problem of coastal squeeze.

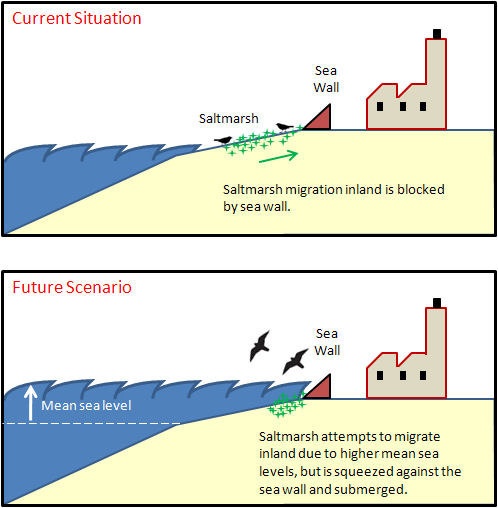

Coastal squeeze

(or in this context saltmarsh squeeze) is the process whereby coastal habitats and natural features are squeezed, and ultimately lost, between rising relative sea levels and hard sea defences (Doody, 2004; Wolters et al., 2005). The rise in sea level causes the low water mark to migrate landward while the high water mark is held stationary by the defence (Figure 1.9). This process reduces the width of the intertidal habitat, which in turn, reduces the buffering effect afforded the defence. The defence gradually becomes more destabilised as the toe is attacked by waves more frequently, and may eventually be undermined requiring large investment in repair costs (Royal Haskoning, 2010).

Ecodynamic design

Retreat the Line – this is also known as Managed Realignment.

Managed Realignment can be applied to many different situations that fall within the scope of coastal and flood management. It is important to be clear on the aim and purpose of the proposed project at the beginning. Without this it may be difficult later to determine the success/failure of the scheme in meeting its objectives. It is also important at the outset of a project to identify any potential opportunities and/or constraints. Managed Realignment presents the opportunity for a variety of benefits, though such opportunities may also have associated constraints. For example, the realignment of the defences of a Natura 2000 site may be unacceptable for the functioning of the system or the disturbance it would cause.

Drivers for Managed Realignments

| Drivers | Constrians |

|---|---|

| Coastal & Flood Management | Consents & Legislation |

| Environmental Benefit | Environmental Issues |

| Water Framework Directive | Funding & Financial Compensation |

| Funding | Opposition from the community |

| Legislation | |

| Navigation |

Costs and benefits

Costs and benefits of a managed realignment project are difficult to determine and can differ from project to project. However, DEFRA (2008) mentions the cost and benefits according to experience of several projects:

The main economic benefits are reduced defence costs, due to both shorter defences and the role of inter-tidal habitats in wave energy reduction. Standard project appraisals aim to account for these benefits but currently existing scientific information on wave energy dissipation over inter-tidal surfaces is not fully utilised in predicting how much lower defences realigned inland could be for different water depths. However, inter-tidal habitats also provide other important products and services that, even though they are often not marketed, have significant economic social value.

Compared to the ‘Holding the Line’ alternative, the situations where Managed Realignment is likely to have the higher net benefits include:

- areas with low value agricultural land;

- sites where the topography allows shorter defences inland or no additional defences where retreat is to higher ground; and

- sites where the topography is such that only minor or no engineering works are necessary to ensure natural succession to the desired type of ecosystem.

Experience shows that the costs of engineering works are likely to be minor compared to land opportunity costs. In some cases, Managed Realignment leads both to the loss of freshwater or brackish habitats and to the creation of salt marshes or mudflats. It is difficult to generalise as to which type of habitat has the higher value, though in some cases one type of habitat may clearly be providing more valuable goods or services.

There is still considerable uncertainty regarding benefits and costs of Managed Realignment. Results from case studies show that costs can be higher than expected, as it is difficult to predict the success of habitat recreation, what further works might be necessary to improve or accelerate habitat succession, and what the cost of maintenance will be. There can also be costly delays in the process of Managed Realignment due to planning complexities that were not foreseen. The benefits of managed versus unmanaged realignment are not always clear. There is no consensus amongst ecologists about whether managed retreat sites lead to higher quality habitats than unmanaged ones. Furthermore, the potential costs of unmanaged realignment are likely to depend on risk communication and accompanying safety measures.

It is worth noting that with climate change and sea level rise, holding the line options are likely to become increasingly costly. Furthermore, Managed Realignment schemes are likely to become increasingly preferable on economic grounds, both along the coast and rivers, as it becomes possible to evaluate sea-defence cost savings more accurately based on scientific information.

For more specific information on costs of managed realignment also see Building with Nature Concept – Managed Realignment